No matter how much I like that Neil Young song, “Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere,” I feel that “nowhere” isn’t the right word. This is not a nowhere; it’s more of a non-place. Karkur, this small town, or ex-village, doesn’t really exist. There’s nothing outside my gate.

I grew up in Tel Aviv. My father grew up in Tel Aviv. His mother too. The two years I spent outside my hometown were in Brooklyn, New York. Roaming the streets of big cities is my only true skill. I’m a champion. I can walk dirty pavements forever, as long as it’s not for sports reasons. But I didn’t want to become my father, or my grandmother, or any other arts and media persona living in a big city. My biggest fear was to become a cliché or not to be able to write my own script with my eyes closed.

There’s another way of telling this, of course. I can tell about that evening, on the lower east side, when I heard the land underneath the concrete calling. I felt it suffocating. It made me sick. Or I can tell about my mother’s parents, who lived on a Kibbutz, and how I felt that my holidays there were true and free, how my body came alive, how much I loved the sun and the smell of my own skin.

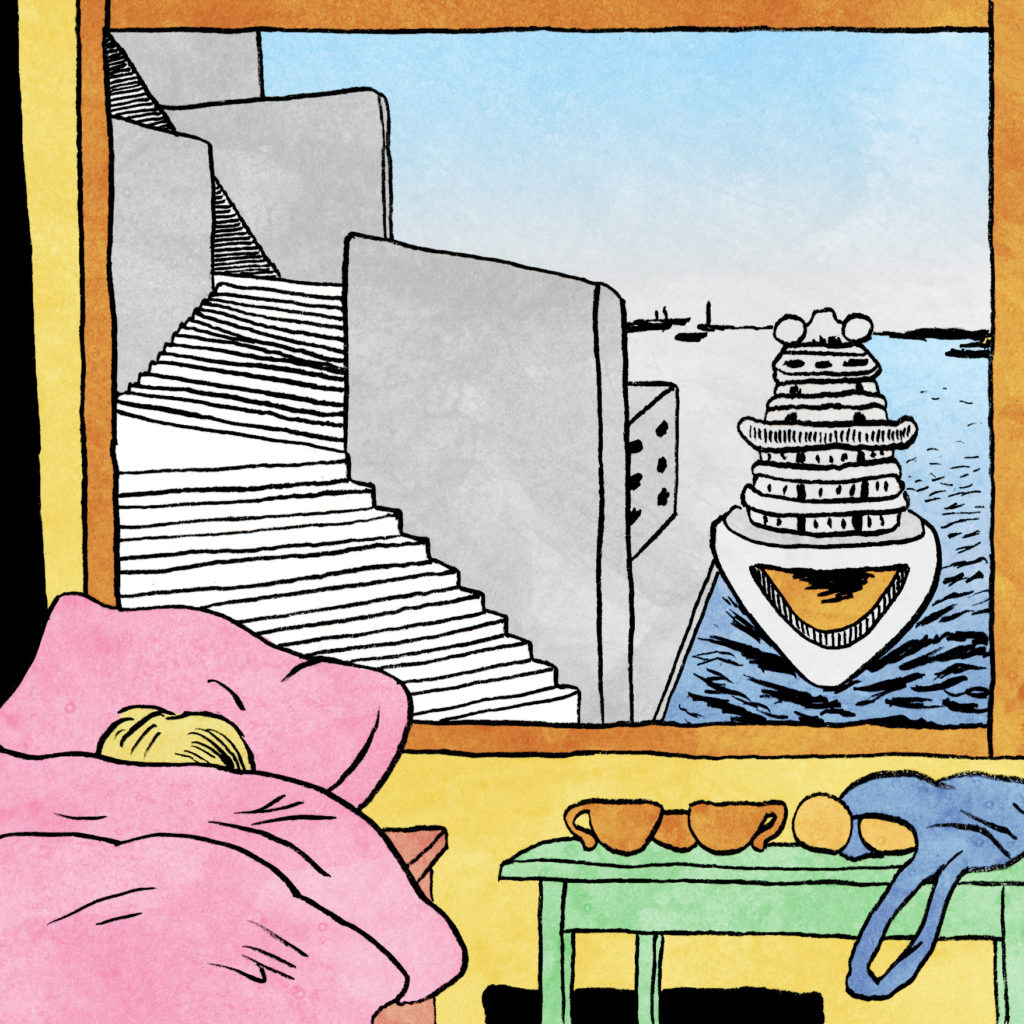

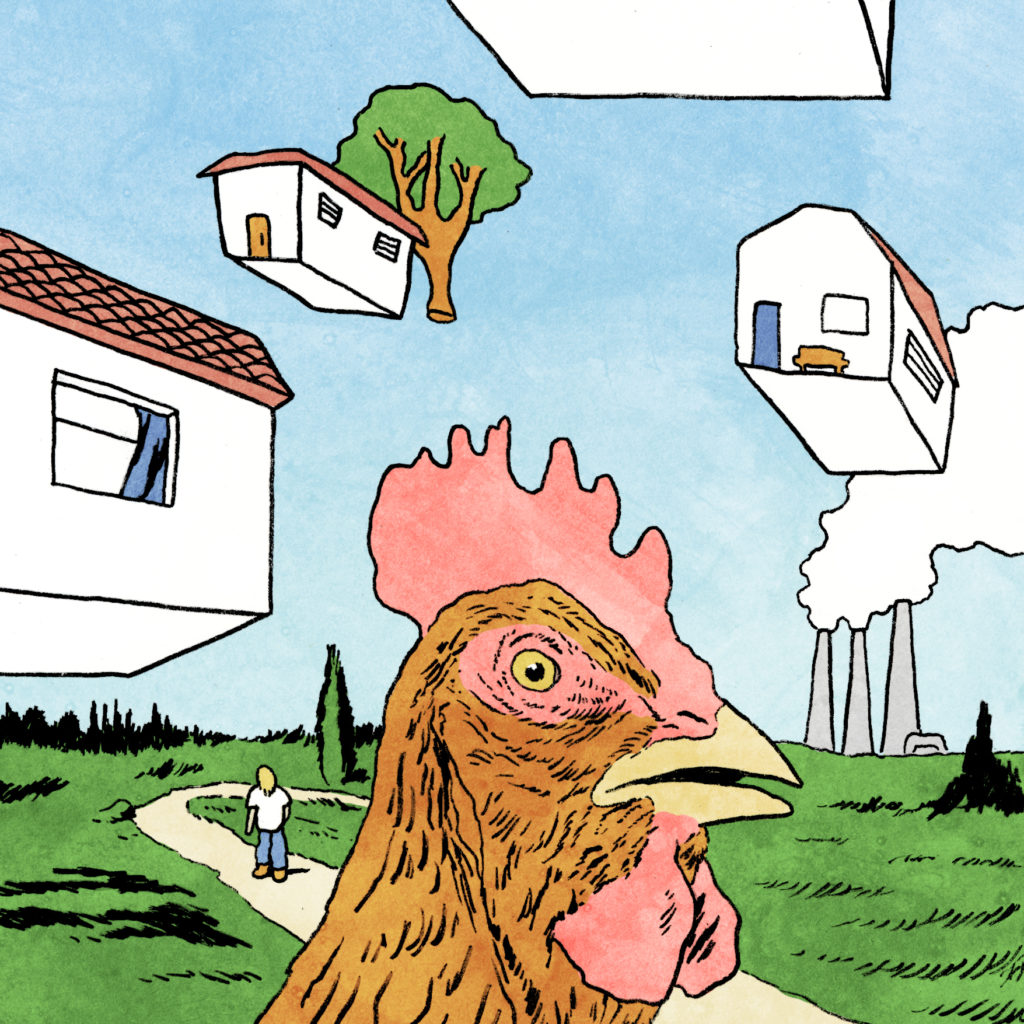

Does it matter why we did what we did? Do reasons matter at all? This is where I live now: In my house, floating in a non-place, not too far from the city. The soil in my yard is breathing the air, and so are my hens and oranges. Not that this air is too clean – Karkur is located about 15 Km from Israel’s largest power station, making many of the green promises grey. So why is it a non-place? Like many aspects of life in the 21st century, it is rapidly changing. We moved here 8 years ago after my second daughter was born, and now, already, we get to be the ones crying about fields turning into shopping malls and little houses turning into 6-story buildings. We are newcomers, but it is usually the natives who like it better with “some civilization” around. I still walk, but I rarely see anyone else walking unless they are “walking” as a form of physical activity or in and out of their cars. Sometimes I feel like I’m the only human inhabiting these surroundings. The rest are 4X4s. Hello Mr. Jeep, and how are you today Ms. Toyota? But there are humans around. I know it because there are other parents in the school, and there are people arguing in local Facebook groups. So everyone else is floating too, in their homes, or in one of those nice cafes around, or in the 2nd hand boutiques, or in yoga lessons, or in the supermarket. They are just moving from one indoor activity – or rustic-style designed space – to the other, and they are almost never seen wandering about, bumping into each other. The enchanting and dangerous power of randomness is missing. It’s a pretty good life for those who know who they are and what they’re doing.

I learned to enjoy walking in the fields near my house. Who wouldn’t like that? It’s green and fresh yet doesn’t impose on you the burden of a spectacular, majestic landscape. It’s cute and homey and possible. I listen to the most beautiful music; I’m grateful for being able to listen to it with my sight focused on a distance. I wear big ugly boots and leave them, muddy, outside my front door when I get back. There are no major attractions here: no museums, no rivers, no spectacular music venues, no mountains, no impressive views of some other place, and no boutique hotels. Nothing to see. Any touristic ventures – except for, maybe, Tantra weekends – are bound to fail. In fact, it is not even clear which part of the country it belongs to: is it the south-north or the west-east. It’s right in the middle, but not in the center. It’s welcoming, but no one really wants to be welcomed. Being a non-place is, in fact, one of its main advantages: a non-place is hardly branded or commoditized. It can merely be itself, and that is, nowadays, quite an achievement. Or unachievement, of course.