I

In March 2020, when the Covid19 pandemic reached Tel-Aviv, imposing with it a nationwide quarantine, a group of women, including myself, set out to collect the heaps of unused produce left by restaurants, cafes, and offices, due to the sudden shutdown. The idea was simple – rescue food that would otherwise go to waste and redistribute it among those entering this period of uncertainty without food security.

This swift operation took three days, during which we located families and seniors in need of support, recruited volunteers, found packing solutions, and raised funds to purchase dry foods to supplement the 400 boxes we’d loaded with rescued produce. While a group of friends ran calls to confirm the addresses of the recipients of our spontaneous food drive, an idea came up to ask the elderly recipients whether they would like to be paired with a buddy for comforting phone conversations during this period. Dozens said yes.

One impromptu action inspired another, and with the sudden vacuum created by the first days of lockdown, messages began pouring in from people wanting to take part, whether by packing, running deliveries, cooking warm meals, or adopting a senior for phone conversations. Although none of us women leading the efforts had any background in community organizing, and while we weren’t planning on continuing beyond the first food drive, we soon realized that, with the human resources at hand, an opportunity had arisen to generate community involvement and care.

Fast forward over two yearslater, our spontaneous initiative to redistribute rescued food rippled into a large scale movement, with thousands of volunteers and dozens of programs — from food drives to home improvements, from telephone programs (that now include single mothers, families at risk, and asylum seekers) to community fridges. We’ve distributed over 80,000 food boxes and over 50,000 hot meals. We opened our own community space, donated to us by the nightlife venue Teder, where we host screenings, talks, and performances concerning the everyday struggles we encounter through our work. The space also facilitates a “radical library” and a meeting place for activists and various community-led initiatives.

Our name is Culture of Solidarity, and our logo is a sunflower, but for the first six months of our existence, we refused to be trademarked. We wanted to believe that a community can work together without being a “brand.” We shared our work through our personal social media pages, and many joined through word of mouth. We waved off questions about becoming an official organization, wanting to keep it grassroots. With the experience of Covid shattering reality as we knew it, exposing the fragility of the social institutions and structures we depended on, it was time to rebel against the old order of things.

We evolved organically into a mutual aid movement, that runs independent of government and city funding and that is critical of the non-profit industrial complex. Our approach, which some deem “radical,” doesn’t stem from youthful naivete — it’s a direct response to our experience with the failures of the institutions to whom we pay taxes, who don’t keep up their end of the deal.

When we first received phone calls from Tel-Aviv social workers, our response was confusion. We were baffled that social workers employed by our city to care for its residents were coming to us — private citizens — to ask for assistance rather than receiving the resources needed from the wealthiest municipality in Israel. But when we started pressing public officials in office for answers, we became furious.

For months we alerted city officials. With adult day-care centers shutting down, many seniors were left with no place to source their meals. Asylum seekers were under eviction threat because, after being laid off from their service industry jobs and deprived of government support, they couldn’t pay rent. Some landlords went as far as damaging the water systems of their own properties to drive families out. Single mothers were calling us in tears, saying that they were caving under accumulating debt and couldn’t even afford baby food.

In one instance, we received information about an elderly man suffering from malnourishment. When a volunteer arrived with freshly cooked food, she discovered he didn’t have a fridge to store it in. We quickly arranged a donation, but when volunteers arrived to set it up, they discovered there wasn’t electricity to plug it into. Without proper support from social services, this senior couldn’t afford his electricity bills and had already been living without power for two months.

We sent lists. Names and addresses of families, seniors, and people living with disabilities that were in acute need of support. We were dragged between departments for months. Finally, we were told that our requests had been processed and would receive appropriate assistance. But when we investigated further into it, we discovered that the “appropriate assistance” didn’t amount to much. In fact, most of these families and seniors had been in the system for years. What we were witnessing wasn’t the result of a pandemic overwhelming social services, it was the result of years of neglect and flawed policies maintained to preserve poverty.

II

In his 2017 song “The Story of OJ,” Jay-Z raps: “You wanna know what’s more important than throwin’ away money at a strip club? Credit. You ever wonder why Jewish people own all the property in America? This how they did it.”

So go the lyrics that launched a thousand tweets and disgruntled the Anti-Defamation League. But, inflated as his claim may be in this parable on upward mobility, it speaks in essence to the nature of survival of marginalized groups in the capitalist superstructure — the idea that wealth can transcend race or ethnicity and offer protection, or as Jay put it, “Financial freedom my only hope.”

This is the story of many Jews, including my grandfather Henek, who survived the Holocaust with nothing to his name and slowly built himself up by banding together with other survivors and investing in low-income housing projects in New York till he accumulated some wealth and status. At the time, there was something revolutionary about a Jew establishing himself as an entrepreneur who was no less gifted than the gentiles who dominated the market. After all, financial prowess has been instrumental to Jewish survival over the course of history.

One could say that Israel’s growth story is a similar tale. Through ethnic solidarity, Jews acquired and conquered land in Palestine and erected cities “from dust,” like the Golem, to shelter them from prosecution. Over time, the country that was considered a beacon of socialism, with cooperatives and government involvement in all aspects of life, underwent a process of privatization and deregulation, allowing its citizenry to increase their wealth in the free market economy. Fear and nationalism propelled it to embrace capitalist ideologies that further established its financial power and regional dominance.

The flourishing of the tech industry in the past twenty years has been a decisive tool in demonstrating the success of Zionism and the persistence of Israel in a region surrounded by enemies. This is the triumph of the peoples who, over the centuries, were excluded from professional guilds and denied the right to own land — a homeland with an ever-growing globally-valued industry, an impressively skilled workforce, and accelerating economic growth.

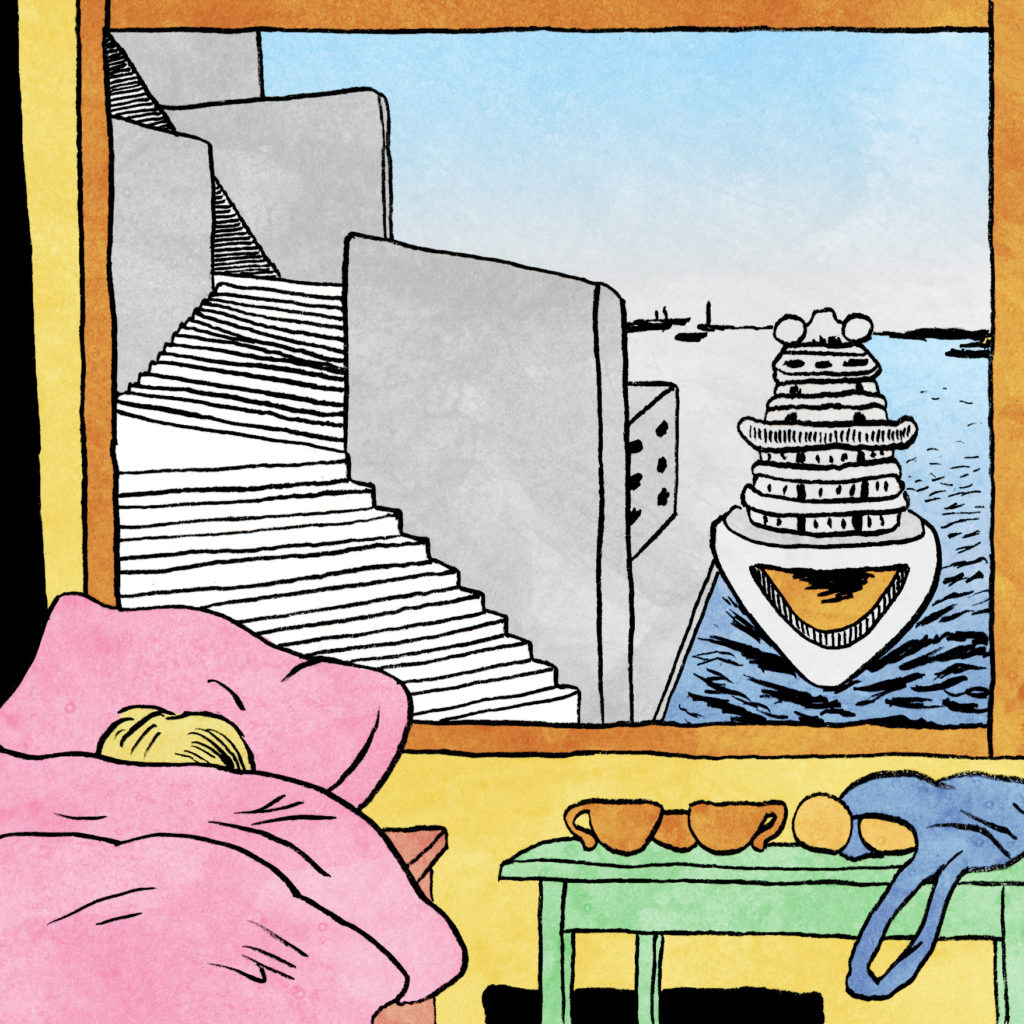

But while Jews worldwide take pride in the “Silicon Wadi” — the successful industry that helped broadcast the country’s status — this neoliberal haven has generated severe deficits in realizing the values of security and freedom for its inhabitants. The tech boom produced a demand for luxury properties, leading prices to soar, and with the local market becoming more responsive to global influences — displacement, gentrification, and evictions are growing phenomena.

This is a global problem, but these phenomena have been exacerbated in Tel-Aviv. Like the mighty Golem, the cultural and economic capital of the Jews has turned offensive. Infinite cranes dominate its skyline, with the riches of the tech sector reverberating throughout the city. High-rise buildings are being erected everywhere and traffic is congested, thanks to the roads being blocked off for months at a time, as workers imported from China lay down the new light rail.

The embeddedness of Tech culture in Tel-Aviv is equally undeniable. In “The First Hebrew City,” Hebrew has been substituted with corporate English. “Community” has moved from the egalitarian ideology on which the country was founded to a marketing trademark for co-working spaces. Artists have become NFT entrepreneurs, and street art now services new developments. Suits race down the city’s new bike paths on e-scooters, plugged to their AirPods.

The face of the city is changing, and so is its populace. As old blocks are being torn down and rebuilt, longtime residents are being forced out due to the shortage of public housing.

The municipality of Tel-Aviv serves its allegiance to real estate tycoons while its coffers overflow. The most recent and painful evidence is the forced removal of the impoverished residents of Givat Amal without fair compensation or an appropriate alternative housing solution, all for the sake of a massive development project by billionaire Yitzhak Tshuva. For decades, the city tried to drive out residents from this valuable piece of land by neglecting to invest in infrastructure and refusing to connect them to water and electricity grids (despite them paying property taxes to the city), until finally, on November 15, 2021, police broke down doors and violently executed the evictions.

A week later and across town, in a small park on Yefet Street in Jaffa, tents were set up by Palestinian single mothers fed up with the shortage of public housing and the radical gentrification process that has taken over their neighborhoods. As Israel’s ultra-wealthy flock to the picturesque port city, lured by its oriental charm, Arab families that have lived there for decades are being priced out, advancing the subsequent erasure of Jaffa’s historical fabric.

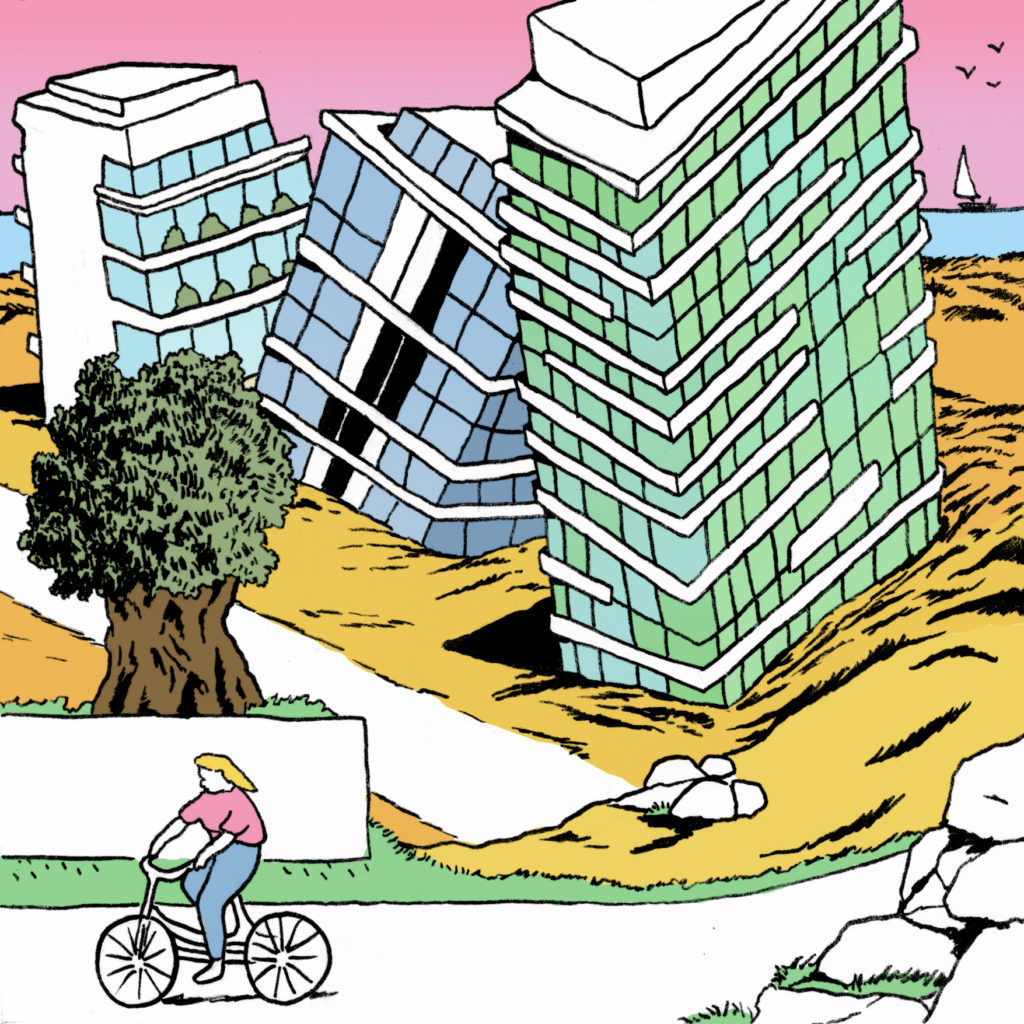

But while many still act as if the housing crisis exists on the margins of society, impacting low-income communities and oppressed people to whom inadequate and unaffordable housing has always been the norm, its symptoms have begun to touch the middle class as well. Households are being squeezed by the cost of living, and first-time homeownership is out of reach for most people without access to generational wealth. Even for highly educated professionals. Even for people working in the tech industry.

They say the hallmark of capitalism is poverty in the midst of plenty – but in Tel-Aviv, it often feels like plenty in the midst of poverty. I would argue that the abundance in the nightlife and culinary scenes of Tel-Aviv are driven by millennials, who have given up on saving and surrendered themselves to the hedonistic city lifestyle, as much as by the new start-up millionaires they break gourmet pita with. With young professionals spending an unsustainable amount of their income on rent, along with increased living costs, saving for the future has become a pipedream to all but the wealthy.

As Tel-Aviv recently topped the charts of the most expensive cities in the world, it’s become a simulacrum of a first-rate modern city — one that is moments away from collapsing into itself.

III

The marriage between tech and nationalism is the essence of Israeli capitalism, with Zionism as the religion we obey that generates an acceptance of the conditions as they are.

Perhaps the single-minded race towards a five-figure a month tech salary is also a means of maintaining oblivion to the fact that the average worker in the open-air prison that is Gaza, which is just an hour drive outside of Tel-Aviv, hardly brings in 700 Shekels a month. Of course, the issue of the Nakba feels out of sight when you’re busy trying to seize opportunities in a booming market or grinding in the capitalist hamster wheel.

But the residential is political, and the shape of housing in Tel-Aviv reflects its class inequalities and exclusionary ethnic hierarchy. Many Tel-Avivians are unaware that their residence is tied to the violent removal of others. But, just like the story of the Golem born out of the dust, the story of Tel-Aviv being born out of sand is fictitious. It was built atop the ruins of abandoned Palestinian villages such as Sheikh Muwannis, Jammusin, Salame, and Summeil. And because Palestinian presence has been widely erased from the urban landscape of the “White City,” it is easy for Tel-Aviv residents to feel far removed from the Occupation, whether of 1967 or 1948.

The removal of Givat Amal residents is another layer in a history of displacement. Before the establishment of Israel, the site of Givat Amal was home to about a thousand Palestinians in the village of al-Jammasin al-Gharbi. After fleeing during the war of 1948, the residents were prevented from returning despite the UN resolution of the right of return, and Israel settled 130 Jewish-Mizrahi families on the village’s ruins.

And now, on the ruins of Givat Amal, which was built on the ruins of al-Jammasin al-Gharb, tall luxury apartment buildings will soon be erected, built with cheap Palestinian labor from the West Bank; some of the workers might even be descendants of those forcefully expelled from those exact grounds. In, will move the new tech millionaires, who will never have to confront the fact that their success was built upon countless cruelties.

IV

Here is my confession: I write these lines from an apartment owned by my family. I live an existence cushioned by generational wealth that is partly owed to real estate. And while my family’s legacy is in no way close to the corporate behemoths that cannibalize affordable housing, I still acknowledge how it affects wider circles of life, in that the commodification of housing, in whatever capacity, means profiting from an unjust system that fundamentally harms the interests of the people.

I live by Sheinkin street, which has recently been rejuvenated. On Sheinkin street, you can complete your weekly shopping by hopping from the boutique bakery to the boutique cheese shop, the boutique butcher, and the boutique greengrocer. When there’s time for leisure, you can ride your bike down Sheinkin and then left down Geula — in less than ten minutes, you’re at the beach. If you wish, you can ride your bike down Sheinkin and then right on Bialik, past the beautiful Bauhaus buildings, and work on your laptop from one of the European-style cafes.

In this little bubble, Tel-Aviv can be quite idyllic. But suppose you ride your bike up Sheinkin, then right across Menachem Begin and into the Neve Sha’anan area, just seven minutes away, you will witness the stark inequality that this city holds between those who own capital and citizen rights and those who don’t.

As someone who believes in distributive justice, my social positioning creates conflicts that I encounter every day, through my work, through engagement with friends and members of my community who were not born into similar advantages, and through the choices I make. My advantages allow me the freedom to commit to a life of community organizing, while many people who should be leading such projects, who actually come from struggle, can’t afford to. It is a big part of the problem when thinking about elite control in tackling socio-political issues.

I understand that an individual act of wealth redistribution can’t change the system, though it’s a big part of it. A broader paradigm shift is needed, and I believe I am a part of a growing movement of people who are looking beyond their bubbles of race and class, rejecting the status quo – the systems that widen economic and racial inequality in the name of nationalism and private capital growth.

In hindsight, it is no surprise that Culture of Solidarity emerged during this era of unprecedented expansion and hyper-commodification in Tel-Aviv. It is the outcome of the knotted tension between young people’s progressive values and the corporate greed that drives the culture around them. It is a response to the underlying urgency for basic stability and corrective alternatives in the midst of excess.

In a sense, Culture of Solidarity offers a new urban imaginary for Tel-Aviv — an experimental microcosm in which we can practice a type of living that goes beyond serving our material interests; that focuses on community uplift through distributive justice and radical care. It is crucial, not only as a moral stance towards the dispossessions and injustices wrought by the city in which we live, but as a practical step towards comprehensive change that revolves around the diversity of social perspectives necessary for human beings to flourish.

In order to construct new social alternatives, we have to speak up against the root causes of inequality while responding in real-time to the changing social currents by making informed decisions through continuous dialogue with the communities we work with. We create opportunities for our community to study the social, political, and economic mechanisms that make up the oppressive systems we live in, holding anti-racist principles as foundational to our collective liberation.

As a mutual aid, we’re fully resourced by our community — whether people contribute their skills, talents, or money, we attempt a different kind of economy — a solidarity economy. With a solidarity economy, we are trying to establish self-reliant community networks. We don’t accept any government or city support, definitely not as a means for them to create a screen of good PR to cover up their failures.

I’m a true believer that revolutions emerge from the fringes — from individuals or groups who take a stand. But I’m also a realist. For now, the emancipatory alternatives to capitalism we practice can only exist in their fullest form in this microcosm we built. I am sending these notes out from a sinking city, where affordable housing has been dismantled, where vulnerable communities face exploitation and insecurity on a daily basis, as well as bearing the health burdens of environmental damages, and where the political apparatus is entirely organized around interest groups. We are up against giants.

But when Tel-Aviv finally sinks, swallowed into the metaverse, perhaps then, we will rediscover our agency. Perhaps we will break free from the shackles of capitalism, maybe even overthrowing the nation-state while we’re at it. Perhaps we will organize around art again, around nature and moral concerns. Perhaps we will invest in our communal prosperity.

Or, perhaps we will move to Haifa..