If anything, this bizarre year has taught us that there’s always room for more screen-time in our lives, especially when we spend most of our days in closed spaces, often alone, probably worried.

It’s no surprise that video games have maintained, and even deepened their status as the number one go-to distraction for millions around the globe, who have been sheltering themselves this past year in virtual worlds from the intense anxiety of a pandemic ridden reality.

This deepening accrued not only in numbers, but also in the blurring of lines between art and gaming, as interactivity became a growing necessity for online art experiences, and gaming furthered it’s search for more complexity.

To get a better grasp on all things between art and gaming, we spoke to Shalev Moran – game designer at PortaPlay, member of the Game Arts International Network collective, designer of the indie game “Archipelago,” video-game exhibition curator and innovator.

*

Hi Shalev! Let’s jump to it. As a video-game designer, artist, and curator, we would love to hear your perspective on the relationship between gaming and art.

Though I’ve been playing video games since I was a child, I never considered myself a “gamer”. I didn’t think of gaming as a part of my cultural background. I saw myself as a visual artist. When I got to Tel-Aviv University, I rediscovered the world of gaming. I also discovered the world of performance art and worked with a few political performance art groups, such as “frontline theatre” and “public movement.”

My renewed interest in gaming didn’t go unnoticed. I was “the gamer” in a super artsy, elitist leftist milieu that finds gaming to be an inferior, commercial type of entertainment. I was eager to prove what artistic potential videogames have. Curating a gaming exhibition was my way of combining two of my greatest passions, while talking to my peers in a language they take more seriously.

It forced me to adopt a more critical eye for gaming as a platform and look at it as a cultural, rather than as a purely commercial medium. As a curator, I suddenly had to start defining and analyzing video games just like any other form of art. I find this mindset to be a valuable tool both as a game designer and a curator.

From an artistic perspective, where do videogames exceed other traditional mediums?

Each medium has its pluses and minuses. Videogames have one significant advantage – It’s high level of audience engagement. This medium forces you to constantly make decisions, getting you more emotionally invested in the story. I think people find gaming so powerful because it allows them to safely answer the question “what would I do if this would happen to me?” or “how would it feel to be there?”. As a storyteller that’s a super-tool. In media studies we describe this super engaged state of mind as “leaning in” instead of “leaning backward.”

The level of immersion and emotional investment gaming offers makes it easier for us to get our messages through. Being in this “leaning in” position lowers the player’s ability to resist or criticize ideas. That’s what turns games into such an effective tool. This feeling of immersion also gives this medium the dangerous potential of getting a player so involved, they might lose their sense of moral judgment.

Plus, there’s the “sandbox” element, which I feel is not as discussed. In old-school mediums such as literature, film, or TV, you’re presented with a story – and that’s it. When you play a video game, the plot is multidimensional, there’s an element of unraveling. It’s an enormous field you can explore. You’re encouraged to unfold the story actively. It’s a narrative tool that almost no other medium offers. I’m not even focusing on the player’s ability to win or lose or control an outcome; It’s more about the player’s presence in the game’s world. Solely being there, in unusual surroundings, as someone or something different. Being able to take your audience there is an exceptional asset for an artist.

That’s why I advise people who dream of writing games to stop focusing on the plot or a linear set of events. Instead, I ask them to focus on situations. What is the situation you’re portraying? How is it to be in that situation? That’s where we outstand other mediums.

And what about the limits? Where do other mediums exceed?

One of the challenges that come to mind when I think about game design today is how fast technology changes. I follow the game-engine arena and keep looking for opportunities to add new effects and features to my games, but at times it feels like I’m chasing my own tail. In a sense, this constant race against an ever-evolving technology harms our attempts to create anything at all. Imagine trying to film a movie while replacing your cameras every month, plus having to build them yourself.

That’s exactly what we must do whenever we change a game-engine just to get that new shiny feature. It doesn’t happen every day, but take an author, for example. Writing a book fifty years ago or ten years ago was a relatively similar process; the computer replaced the typewriter, but words are words, a keyboard is a keyboard. Yet we as game designers keep having to change the way we work, the tools we use, languages, technologies – they constantly evolve, and we must catch up and adjust our plans accordingly.

As part of an industry that’s rooted in technology, criticizing technological development sounds a bit ironic.

In the world of gaming there’s a significant emphasis on getting as close to reality as possible. Saying, “wow! the graphics are amazing!” usually means, “wow! this game looks more realistic than last year’s game!”

I find our fixation on naturalism very technical. Think about the great ideals of art; naturalism was just one, and not necessarily the most significant one. We evolved our creative techniques throughout history. We learned how to create art that’s closer and closer to reality – but it wasn’t the ideal. It was another tool we used to express ourselves.

In my opinion, making realism, a relatively minor cultural movement from 150 years ago – our holy grail, is somewhat superficial.

I mean, of-course we’re chasing those innovative technologies, but I find real innovation in ideas rather than in engines. That’s pure beauty to me, an original point of view.

I wonder how much more challenging it is to share complex ideas with an audience that isn’t the typical artsy archetype. Can this dialog be frustrating at times?

I try to let go. I take a deep breath, bite my lips, and remind myself that my work, whether it’s a game or an exhibition – is always open to interpretation. There’s no way for me to force people to see things exactly as I see them, And that’s ok. The audience takes what they take from a piece, and I try embracing this reality instead of fighting it. Eventually, some people find in my work beautiful meanings I never considered.

Can you give an example?

My first exhibition was named “right arrow”. It took place at the 2013 “print screen” festival. I curated a series of side scroller games, simple games where the player moves from one side of the screen to the other, like in Super Mario. One of these games was developed by a group of Israeli students, and on the opening night, one of them approached me and said, “I read what you’ve written about my game, and I must thank you for mentioning ideas that I didn’t even consider when I created this game.”

It was very flattering, of course, but it has also taught me an important lesson. Just as I accidentally found unintended personal meaning in that artist’s creation, other people might find something meaningful of their own in one of my works. As I receive feedback from viewers, I understand the importance of giving my audience some credit. Whether they enjoy my art on a superficial level or in a more complex, meaningful way, all I can do is try to create truth. It’s more than entertainment; it’s an opportunity to take an in-depth look at things that matter to me. The rest is out of my control.

When I create a game, I do my best to avoid unnecessary extra “fat,” and include only elements that serve a purpose.

*

Shalev Moran recommends:

The recent hit in the art-game world is Blaseball, an online game that is basically fantasy-baseball betting. The trick is that it is *actually* fantasy, with all kinds of outlandish things happening to the different teams throughout the very rapid seasons, and the player community gets to vote and affect every decision together.

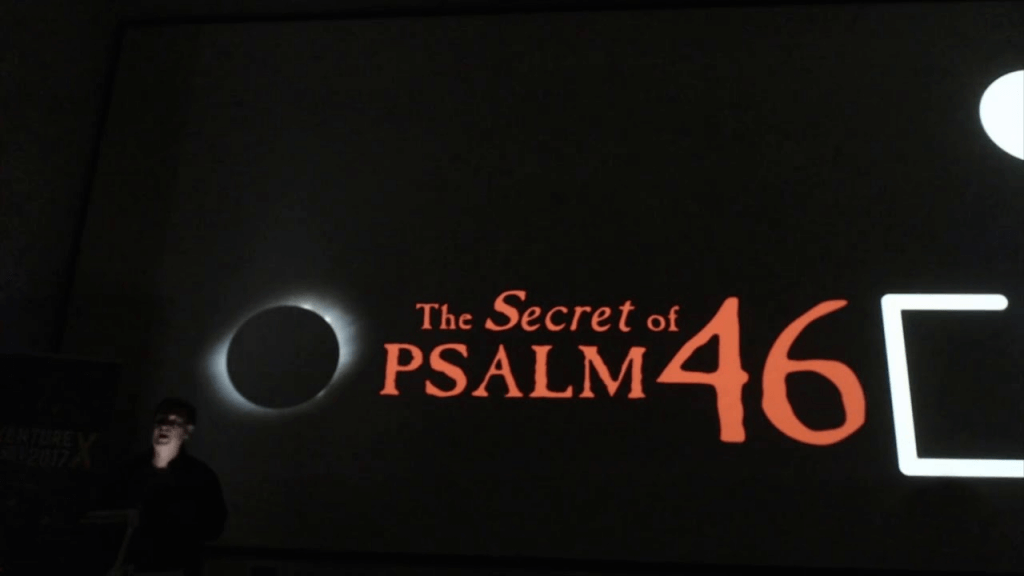

The Secret of Psalm 46 has gained somewhat of a cult classic status in the world of videogames, even though it is only a lecture. Originally delivered in 2002 by game designer Brian Moriarty, it blends children’s books and Shakespeare, adventure games and the bible, together with Moriarty’s own biography. It has a dramatic flare that stays fresh almost 20 years after it was written.

*