“The Negev is our natural space of action, it’s not just a choice of residence. It’s truly an identity, a mission in many ways. I belong to the Negev; I want to promote it. The periphery is the place that stimulates and interests me, where I feel we can act in a way that can truly change the world for the better,” says curator and artist Sofie Berzon MacKie from Kibbutz Be’eri. She serves as a curator at the Be’eri Gallery. along with artist and curator Dr. Ziva Jellin.

Be’eri Gallery was established in 1986 in Kibbutz Be’eri in the Negev, in honor of the 40th anniversary of the Kibbutz’s founding. Since then until this past October, it has been a gem of art in the periphery, presenting about 400 exhibitions and showcasing works by some of Israel’s best artists.

Survivors of the October 7th terror attack in the Be’eri community are now taking refuge in hotels and trying to rebuild their lives. However, not only people have found themselves refugees in their own country, but also the culture that these communities have created and nurtured for years has remained uprooted and without a home. This includes Be’eri Gallery, which was completely destroyed by the terrorists.

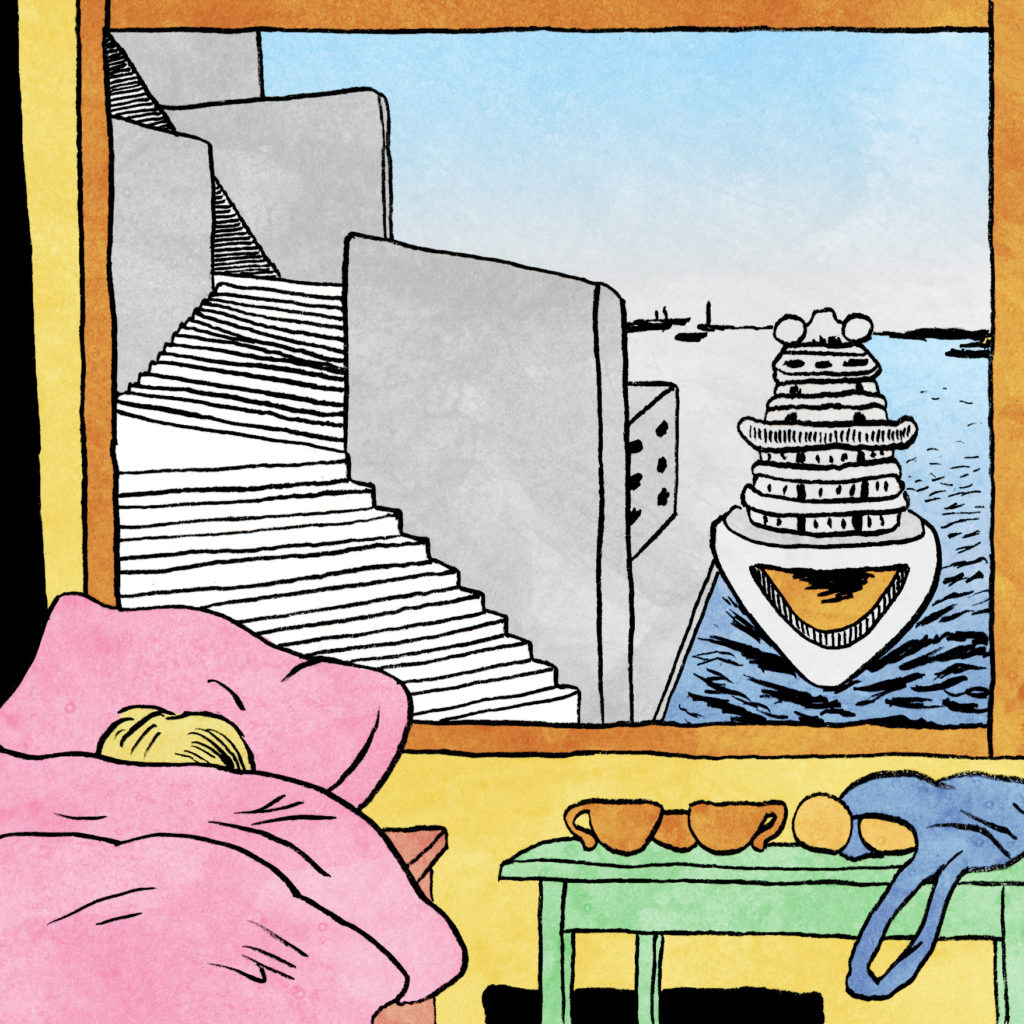

The art world has come to the aid of the Gallery with unprecedented support. Recently, it was announced that in February 2024, the gallery will move to a temporary venue in the Teder complex in Beit Romano – one of the most popular and beloved complexes in Tel Aviv – for 3 years. The space is currently undergoing renovations, and during its stay there, Be’eri Gallery will not have to pay rent (thanks to the initiative of the YBOX real estate company, which owns the building) or property tax (thanks to the initiative of the Tel Aviv Municipality and the city’s cultural advisor, Dr. Revital Ben-Asher Peretz, who initiated the move).

The exhibition plan for the next 8 months will stay the same, and will feature works by Mati Elmaliach, Haim Maor, Gabriella Klein, Milly Barzellai, Yael Hovav (winner of ‘Fresh Paint’ competition), Idit Fisher Katz, Ayelet Hashachar Cohen and an exhibition by an outstanding student from Sapir College, as part of the long-standing collaboration between the gallery and the college. Meanwhile, the gallery will also be rebuilt in the kibbutz, thanks in part to a generous donation from the German government. In the midst of difficult circumstances, the gallery will try to find a home for itself in the heart of Tel Aviv.

When we think about exhibition spaces, we tend to attribute their identity solely to their physical borders. As if that identity starts and ends between the gallery walls and in the mind of its operators. In reality, every exhibition space has a “character” created by both overt and covert connections of different kinds. These create a kind of entity in itself, hovering above all actions and decisions made within said space. While Tel Aviv is generally perceived by us as a relatively “neutral” space for artistic action, the choice to operate outside Tel Aviv automatically claims the gallery’s “entity”, dictated by various factors, stemming from the geographical and human context surrounding it.

In an attempt to transplant a piece of the essence from Be’eri Gallery to Tel Aviv, the ideas shaping the exhibition space stand out at a level that cannot be ignored, which brings the questions underlying the gallery’s foundation to the surface. For example, in the natural and immediate environment of the southern gallery, questions like ‘What can Be’eri Gallery offer to the residents of the Negev?’ are natural and self-evident. When the gallery is located in the heart of Tel Aviv’s nightlife and culture scene, the question demands renewed discussion.

“Yes, suddenly that’s the question”, emphasizes Berzon MacKie. “Art is a global language, but the space in which it takes place is critical. In what ways will it be different? I don’t know, we’re not there yet. But it’s clear to me that very meaningful questions need to be answered. And the time to ask them has not come until now, as we were dealing with… you know. We are still refugees in the Dead Sea, we have no home, and the community has gone through what it has. The dead we had to bury, the captives that are not all back with us yet. We are in the midst of the process”.

“And then, in the middle of it all, trying to build some sort of future, with the understanding that we are building it so that we can bring it back home. We want to continue to be something meaningful for the Negev, for the Be’eri community, for the entire south of Israel. Questions like how to define it now are part of our journey,” she pauses for a moment. She talks about plans to make a “meaningful act” and wonders if it counts as pretentious in the current setting. But maybe keeping the flame burning is enough for now, and for a whole lot of people it’s much more than that.

“We’re taking what’s dear to us and giving it for safekeeping in the loving hands of Tel Aviv and all our partners on the way. We want to keep the gallery open, so we’ll be able to respond to everything that is happening to us, personally and politically. We wish to bring it back home as a living, breathing thing”, she summarizes. “And on a smaller scale, for Sofie. I found myself after this horrifying trauma thrown out of my own home, with no place to come back to. After all that, reading the news at night and discovering that the gallery was also destroyed – it was a huge shock. You feel like you have nothing in the world. I have my children with me, but everything else was taken from me”.

“How will I get up? How will I continue to live, and for what? Very deep and meaningful questions arise – and the answer to them, for me, was the gallery. It’s something I could do, with people I share a language and worldview with, and we could strive towards some goal. You want to get back a bit of what they stole from you. After I saw that the building was destroyed, I understood that, in essence, what is this gallery? It’s an idea. Just as the violence that destroyed it was an idea, an ideology, art is also an ideology. And it’s the exact opposite of what they did: it’s a force of vitality, renewal, movement, and flow. And this – we need to bring back to the world”, she says.

The current situation is difficult, but it also holds potential. Through the breakdown of reality as we know it, there is an opportunity to thoroughly examine our ethical code and fix its bugs. To rethink the structures and ways in which things have worked so far. Berzon MacKie excitedly talks about the changes she sees unfolding in the art world. They will rebuild the gallery, she says, but it’s important for her to emphasize that the intention is not to bring back the exact same things. “I hope we won’t turn the wheel back in any way – politically, socially. The past isn’t perfect – it led to this situation, after all! We need to aspire to something else, something new,” she says assertively. “What is it, and how should it look? We need to build it. So yes, it’s also an opportunity. If we find ourselves in another ten years without having complicated some deep changes in our local art scene, then we are truly lost”.

“We cannot go back to intrigues, hierarchies, and the most basic lack of understanding that we are connected to each other. The success of each of us is the success of all others. Our ability to do meaningful work is connected to the ability to create a broad collaboration. This is exciting stuff and it’s ok to get excited about it. Suddenly spaces are hosting other spaces. Collaborations are being woven. The map of the art world is opening up to what exists in the south, which is half of Israel’s territory – and there are creators and initiatives there. And maybe one of the most meaningful actions we can take is to work hard to ensure that the walls that fell between people, spaces, and worldviews – will not be rebuilt”.

So, what ideas should lead the way for the art world after October 7th? We can start by recalling the ability of art to offer healing, to add flavor and color to life. Berzon MacKie dismisses the idea of art lacking a foundation of healing, adding that generations of male lecturers defined it as lowly – “but it’s not. Because, due to being immersed in such a routine, we forgot the basics. People create art from some internal healing, and healing is not a bad word in the context of art”.

She describes the question that was almost transparent before – What is the meaning of things – as one of the central questions that the art world will need to address from now on. “This is true for Israel and also for the entire world. What is the meaning of art in times of war? What roles can it have in the midst of a disaster like this? There is a new clarity that brings us back to the core questions. Suddenly, everything we do ceases to look like a natural force and reveals itself for what it is: ideas that can be replaced. Different decisions can be made. Our world – it can be shaped. We have been demonstrating in the streets for so long, and it feels as if it’s so difficult to move the structure of reality, but the opportunity is here. And art needs to return to its true purpose, to what it really needs to do in the world. Every art space, every artist, every curator needs to ask these questions, and we need to answer them together”.

For quite a few years, a significant part of the art world has been ‘art looking at itself in the mirror and making faces’. But at the end of the day, art is a tool for processing, for reflection. Art has somewhat forgotten that it has a role for people.

“This type of art you are describing has always been questionable in my eyes. Some reactions in the art world really raise question marks. Things that were done but were so out of place that it would have been better if they hadn’t been done. It becomes clear that there are times when you need to be silent. You don’t always have to be in action. All the decay of our capitalist, intrusive society, with phones everywhere… everything converged into this event. It’s a Holocaust on live broadcast, with the cameras of the big brother”.

It’s like you’re doing this so that no one else will do it before you.

“Exactly! And one of the most important roles that the art world can take on now is to dare to stop. To process. To pause. To digest. Almost every artistic action that has been done so far has been a resounding failure, devoid of any artistic value. Art is a reflection. When you don’t do that, it’s something else, not art. And now the world is flooded with so much non-art like that. I truly think that we all need to be careful, to give time to processes. To ask: What, why, where, when, in what way – questions that are fundamental in art as well, and an important part of what art has to offer to the world. When these questions are not asked, you just get terrible art.

Can’t we just stop everything for a moment? What’s with all these actions happening? It’s only been two months! It’s a Biblical-scale event, there’s no rush. The only necessary reactions were therapeutic and specific. I was left without a home – that’s urgent. I was in a very difficult emotional state – it was urgent. My children – urgent. Everything else, even collecting testimonies a week later, creates so much unnecessary distress”.

“So when they ask us in the gallery how we will react to it… I allow myself to say that I don’t know yet. Something happened, I don’t know its full consequences, and I’m taking the time to respond responsibly. First we will understand what the questions are, together. There’s no need to hurry all the time to production, to an exhibition, to creation. We want to give ourselves the time for interpretation, and that’s why we haven’t changed our plan: there are 8 planned exhibitions, and we will carry them out. There are artists we continue to work with. What kind of exhibitions will they be? What other actions will be taken? And what’s the connection to the South? All these questions will be answered. In time”.