Our generation, X through Z, missed out on all the great wars. In its stead we got a heavy dose of cartoons, comics and videogames, depicting the most exquisite of fantastical violence. We had the privilege to take in violence through the mediation of any medium of our choice, be it blasted through cathode ray tube or printed with ink on smooth glossy paper, without all the bloody consequences. We were born in the most peaceful period in human history, they say. At least for the west. The west is the best.

Here in the middle east (and for one fateful day in NYC, more on that later) we got to endure lower doses of the thing. Taking the form of terrorisms, sublimating the violence to an aspect of reality, not a state of the world. With the latest developments classic, direct conflicts have started to edge their way to the west, and it feels like the western narrative is starting to blend into a middle-eastern reality. Things have started to change again.

I’m just trying to figure out what the hell is going on. Me, the utopian pacifist who barely believes in the concept of nations, but understand the psycho-magical nature storytelling has on the minds of the masses. I’m trying to make sense of this strange new violent world. The question in me that is stirring most strongly these days – why war? Started out as a simple google search one day and leading me to a letter Einstein wrote to Freud in 1933.

In his letter, simply titled ‘Why War’, Einstein asked: “How is it these devices (society and religion) succeed so well in rousing men to such wild enthusiasm, even to sacrifice their lives? Only one answer is possible. Because man has within him a lust for hatred and destruction. In normal times this passion exists in a latent state, it emerges only in unusual circumstances; but it is a comparatively easy task to call it into play and raise it to the power of a collective psychosis…”

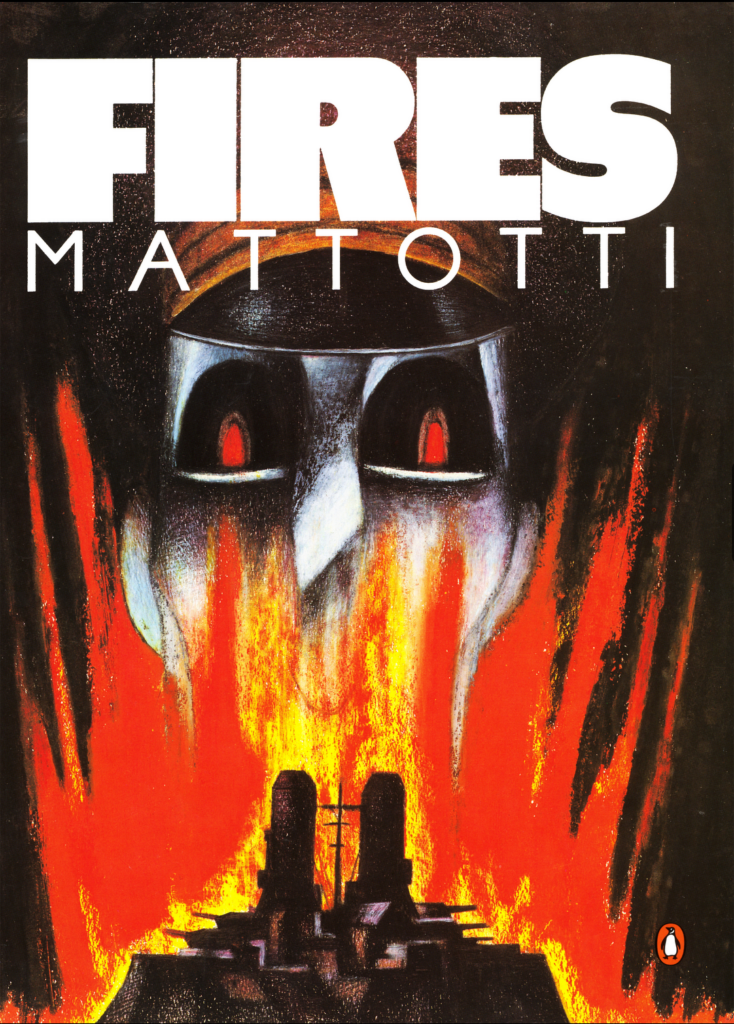

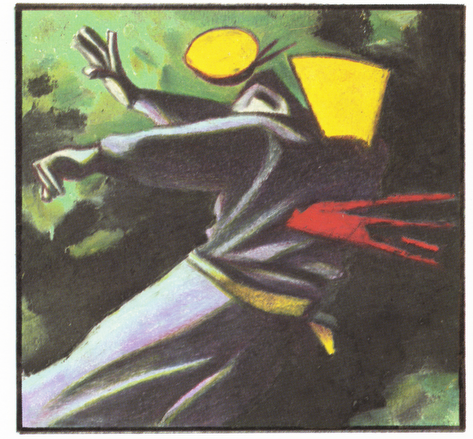

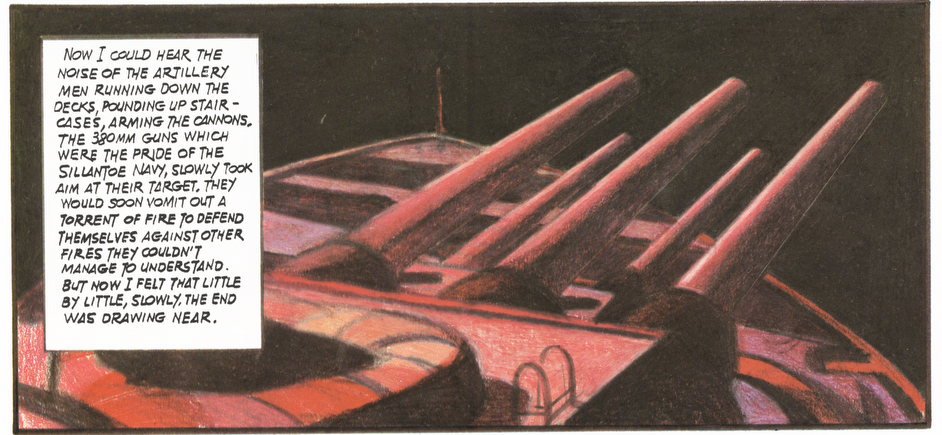

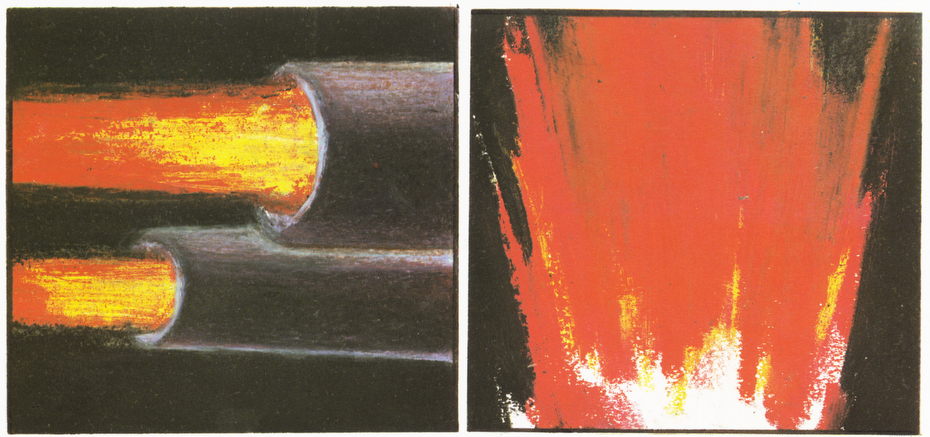

In Lorenso Mattotti’s 1986’s fairytale war story Fires, The narrative concerns a Colonel Absinthe who serves on the ship Anselm II. A warship on a mission to assess and possibly to eliminate the natives of the island of Saint Agatha, which is about to be annexed by the “new state of Sillantoe.” Slowly, the Colonel starts to heed the call of the island, which cries out to him from his dreams, in form of mystical fires and twin figures. Eventfully, he turns native, vows to protect the island, and starts killing and his fellow crewmates.

The graceful and expressive nature of Mattotti’s pastel art, along with his strong use of a distinctive color pallet, almost hides the savage and violent narrative, as it is punctuated by death and casual destruction, with only the briefest moments of hallucinatory bliss.

Mattotti’s graceful narration eventually informs us that the colonizers “would soon vomit out a torrent of fire to defend themselves against other fires they couldn’t manage to understand.”

It is a brutal allegorical war story that ultimately moves away from the colonization narrative and instead focuses on the psychological battle and inner demons, rather than a tangible conflict. An epic fairytale of a post traumatic man in the suburbs, a war of bright fire phantoms of the mind.

World War I, reverently referred to as The Great War, could be considered the birth of modern warfare. With unimaginable scale, scope of destruction, and sheer amounts human suffering. Over a century having passed by, we can reflect on it with with myth-like wonder of a time long, long time ago.

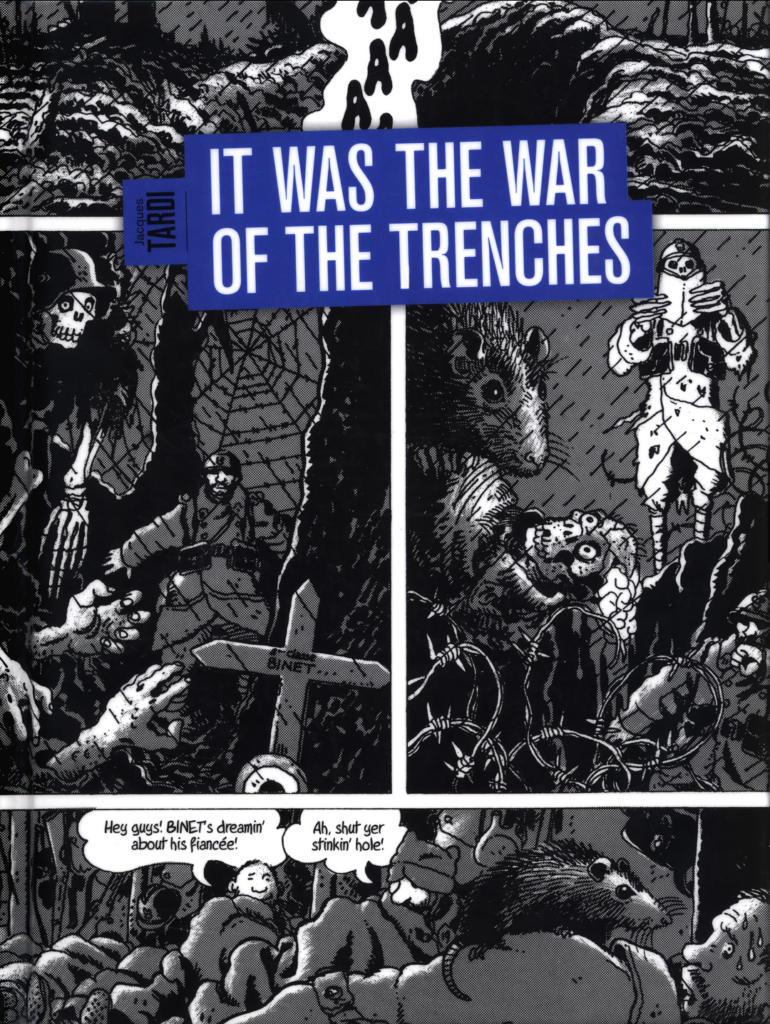

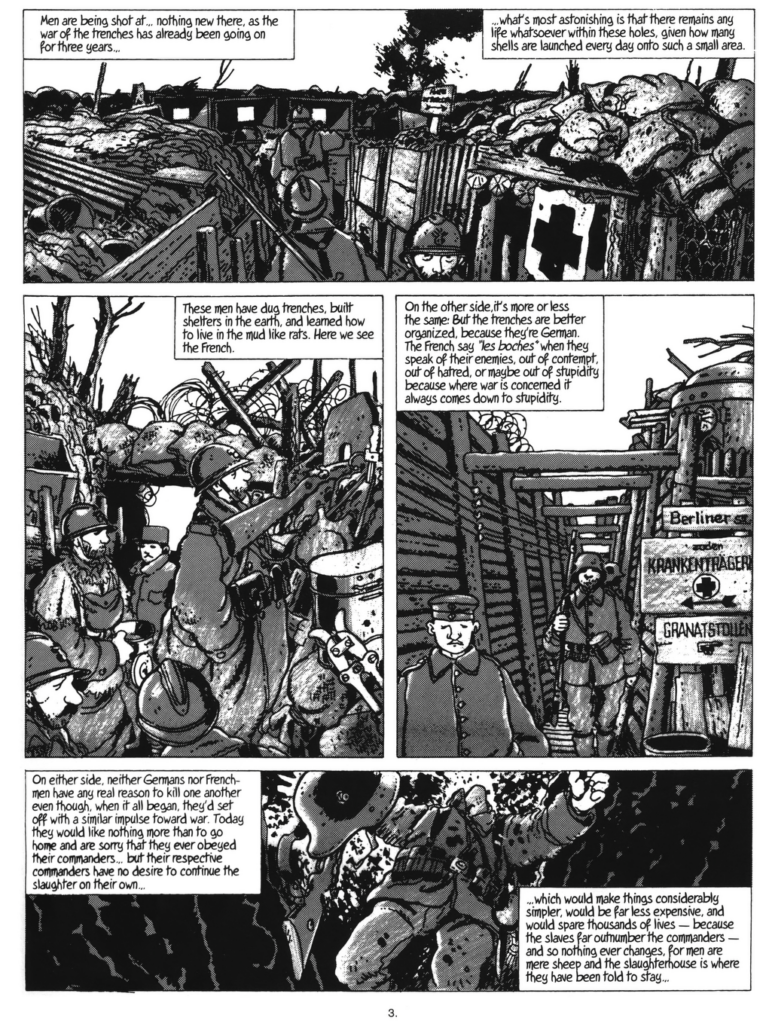

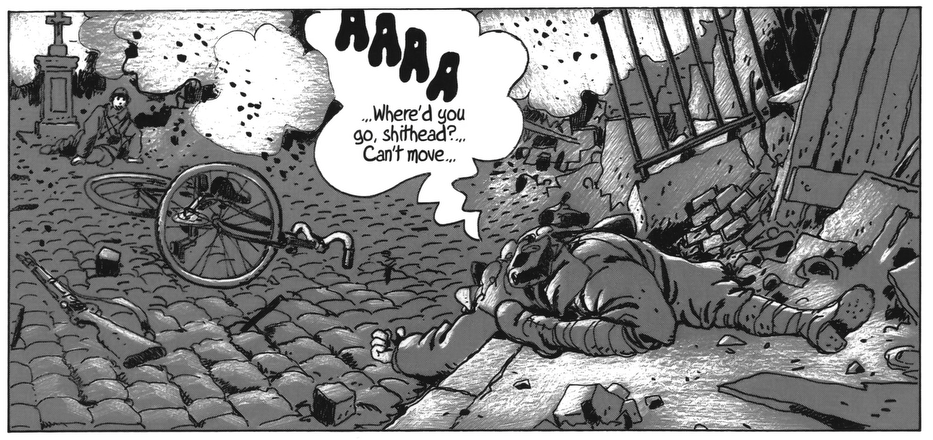

Jacque Tardi’s masterpiece “It as the war of the trenches”, published in France in 1993, translated to English in 2010. Derived from his fascination with his grandfather’s stories, gave me a wider glimpse into that collective psychosis Einstein so curiously ruminated on. In it he carries us through one of the worst episodes in human history from a strictly French existentialist perspective. Tardi consulted historians, piles of books and photo references. Using a cold dead illustrative line, with thick layer of muddy greys, draws a surreal and yet grounded journey though the bloody trenches of the war.

A series of short stabs, tiny personal stories. Chapter breaks are denoted by a simple month and year, what those dates might mean to the grand scheme of the plot can probably be found rotting away in a dark forgotten corner of a history book that inspired the vignette.

The sober voice of the omniscient narration offers a comforting throughline, keeping the insanity of the story from falling into complete raving madness.

Bodies of rats, as well as men gather in piles. There is no obvious distinction between good and evil, enemies and friends are the happenstance of circumstance. The only main character to speak of is that of collective suffering and mass hallucination. Just transitory glimpses into random soldiers’ lives that for the most part end abruptly, painfully and pointlessly.

Of one of the characters it’s told that “Binet, a creature of chance doesn’t care which side he would be fighting for, there’s no meaning anyways. “Later, ironically his dreams are haunted by the unknown fate of his fellow soldier. He goes searching for him, only to find his cold body laying lifeless in the mud proceeds to be shot down in the following panel.

The futility of it all haunts every crevice of that war, the haunting horrors and harrowing screams play out freely while short glimpses of hope are mostly crushed by the reality of the ruthless situation.

In the introduction the author writes: “The only thing that interests me is man and his suffering, and it fills me with rage. This our history, Europe’s history, and the 20th century’s… “

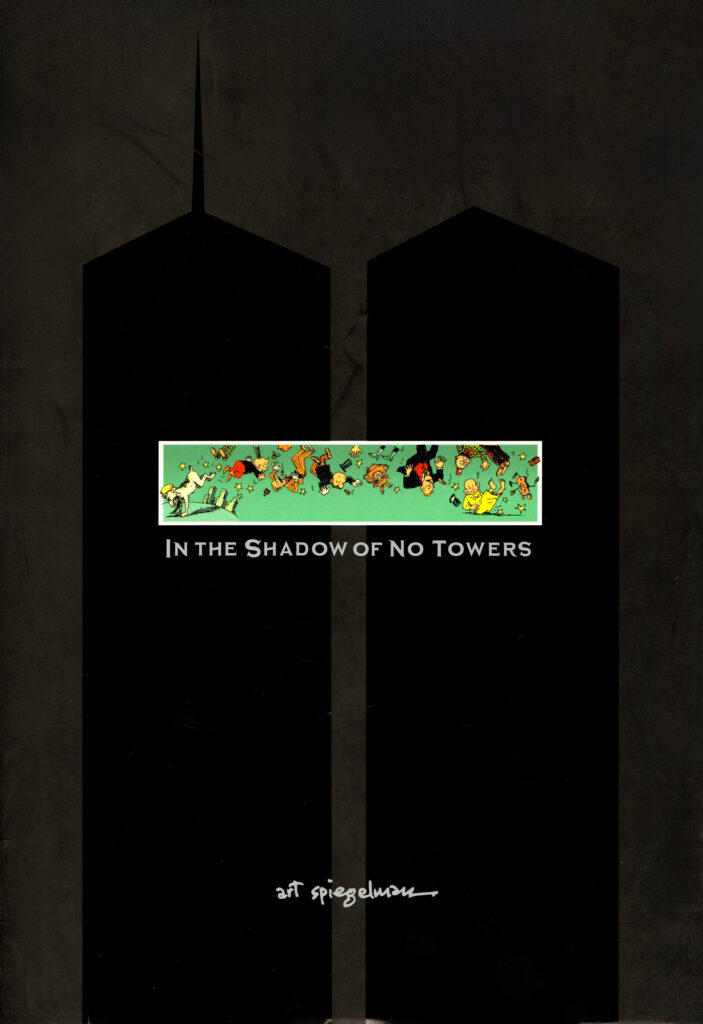

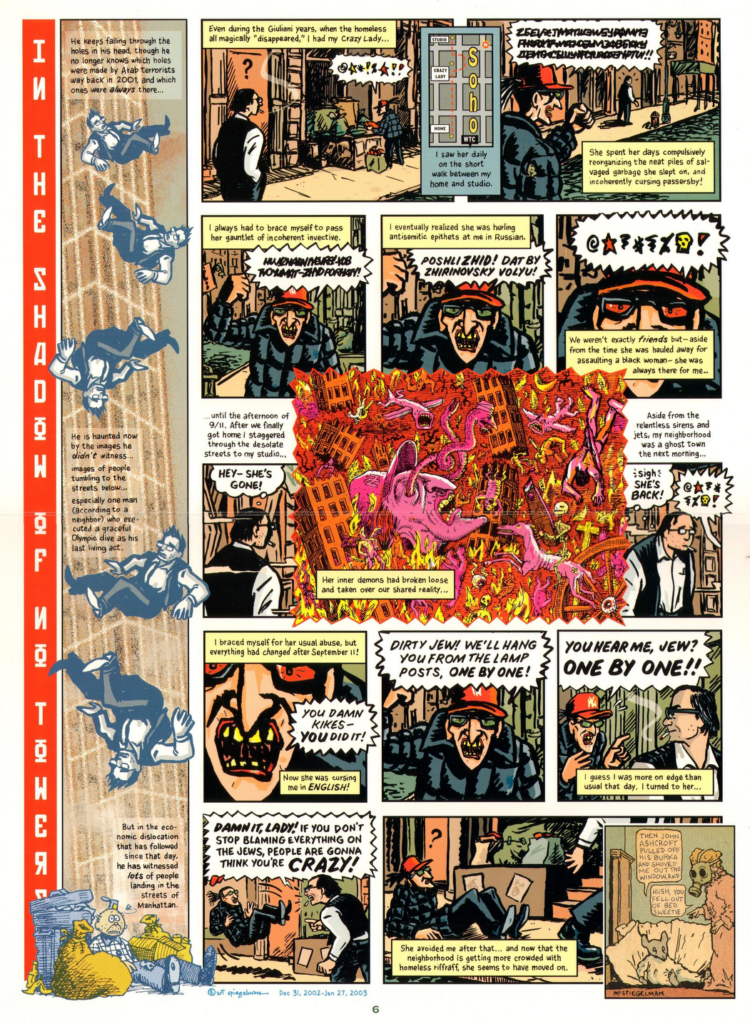

In the 2000’s war started to take on it’s modern incarnations, and the new and improved spectacle of terrorism took the spotlight in favor of traditional warfare. I think the perspective of Art Spiegelman, himself the son of a holocaust survivor, gave me the most insight in the current state of affairs we have been living through in the middle east dealing with a traumatic day with his 2004, lesser known treatise.

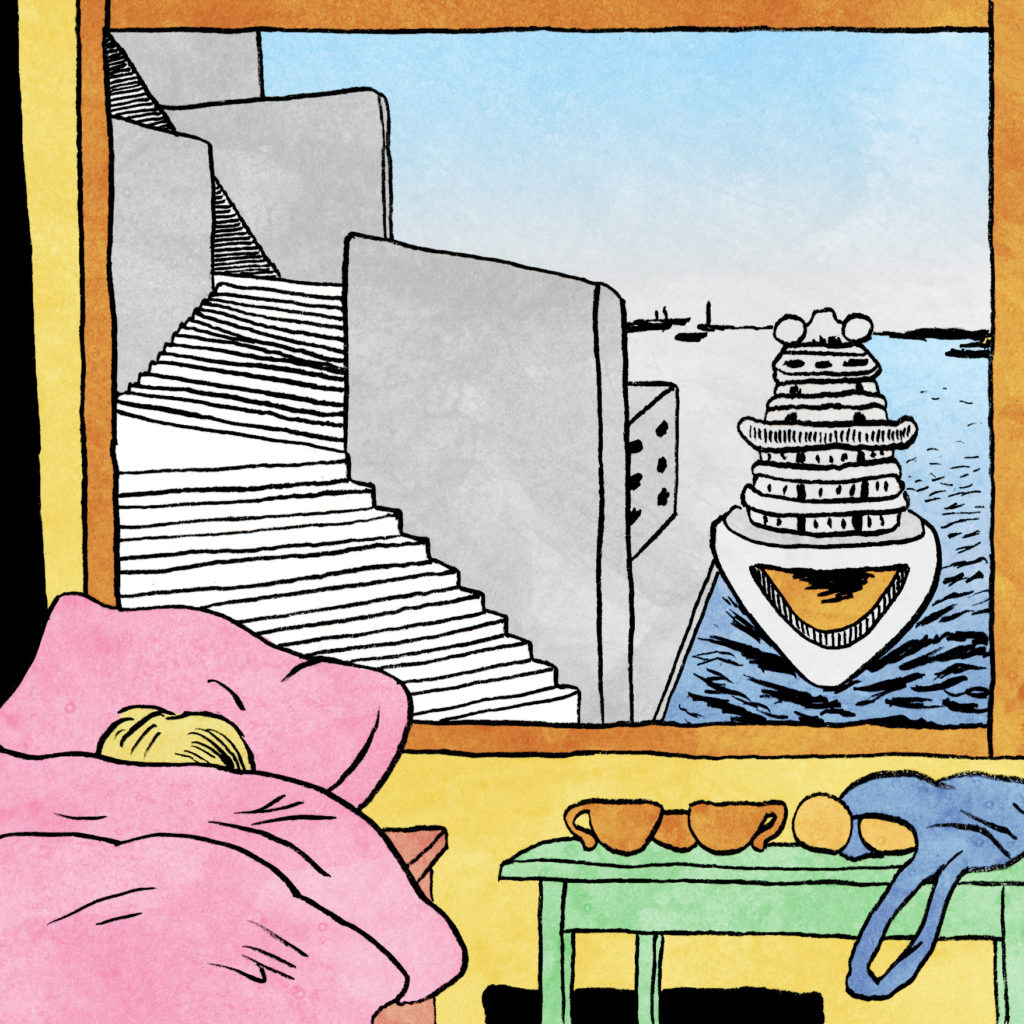

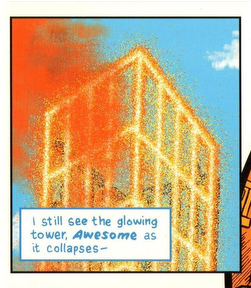

In the shadow of no towers, serialized in the German newspaper Die Zeit 2002-2004, because no other American publication would dare carry a comic of such anti-patriotic sentiment at the time (additionally an excerpt did appear in an Israeli comics Actus Tragicus anthology Dead Haring.) Told from a violently intimate first person perspective, recounting his experiences from the day of and the trauma that followed after witnessing the twin towers fall from the sky in 2001. Each page is haunted by the searing, smoldering skeleton grid of the building, a repeated image on every page of the book .

The book object in a statement in itself, is in the shape of a black slab with pages made of the thickest cardboard, is as much a therapy session for its author as it is a work of comics art that chronicles his transition from one life into another. All while trying to aspire to the spirit of the classic Sunday comic pages.

The series does end with a somber but bright note of acceptance. The trauma of the event might never completely disappear, but seems to fade further into the distance as time goes on.

I’m still trying to figure it all out really, I’m not sure it’ll ever make sense. The simple question of why war that started this piece continues to loom over me with no clear answer. I do think The specific temporal qualities of comics is a uniquely intimate medium to tackle trauma, war, and horror. The reader has total control over the page, with the ability to linger on and leaf through at the speed of their own choice giving them the page. Total control over the events that are undeniably difficult. As to the question that started this whole thing out I’m mostly at a loss for words and Freud’s answer never really satisfied me.

In the closing paragraph Sigmund Freud wrote to Einstein: “As long as all international conflicts are not subject to arbitration and the enforcement of decisions arrived at by arbitration is not guaranteed, and as long as war production is not prohibited we may be sure that war will follow upon war. Unless our civilization achieves the moral strength to overcome this evil, it is bound to share the fate of former civilizations: decline and decay.”